A Georgist Success Story

by Stephen Hoskins, @GeorgistSteve

Initially published here: https://progressandpoverty.substack.com/p/singapore-economic-prosperity-through

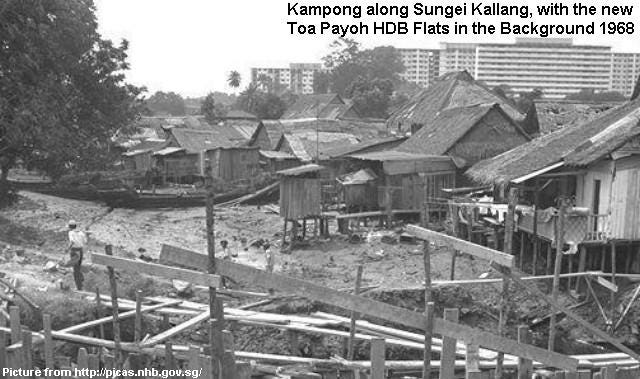

The world if we captured land value

Singapore’s founding mythology goes as follows. After the departure of the British Empire from Singapore and its expulsion from the Federation of Malaysia in 1965, the island nation faced a litany of challenges: a population with low literacy rates, living in kampong-style informal dwellings or crowded shophouses, with wide divisions across ethnic and political lines, under constant threat of military confrontation by large neighbouring states. Enter Lee Kuan Yew (LKY), Singapore’s first Prime Minister, whose bold statesmanship would rapidly propel the ‘little red dot’ to become a unified, multicultural, prosperous nation. At least, that’s the story the nation tells itself. For the most part, this narrative is correct: Singapore today is world-renowned for its competitive business environment, sustained by the culinary delights of hawker centers, clean streets and lush greenery, all knit together by an efficient transportation network.

Less agreed-upon is the question of how exactly this was achieved. Libertarians like to associate Singapore’s success with laissez-faire capitalism; those on the left argue that this perspective ignores Singapore’s bold history of industrial policy. As a matter of fact, both of these narratives-of-convenience overlook the vital core of Singapore’s economic policy. In this article, I’ll demonstrate that the key factor behind Singapore’s success is a set of policies firmly guided by the Georgist mindset of capturing and sharing land value. We will look at the way in which Singapore’s land was restored into public hands, deployed to build wealth, and redistributed through a near-universal program of subsidised housing.

The basic ideas of Henry George have been implemented, in effect .... and interestingly constitute the core of economic and social policy for Singapore.

- Phang Sock Yong, Professor of Economics, Singapore Management University

From the Kampong to HDB

How Singapore Recaptured Land Value To many Georgists, 1965 Singapore may have appeared poised to repeat the mistakes of many states gone before. Fewer than 10% of the population owned property; this small group was likely excited to extract rents from kampong-dwellers and enjoy speculative growth in the value of their land as Singapore developed. But that was not to be Singapore’s path.

Instead, in 1966, the government passed the Land Acquisition Act, granting broad powers to acquire land “for any public purpose”. Crucially, the rate of compensation to be paid to landowners was fixed at the land’s value on the ‘statutory’ date of 30th November 1973. Freezing the price of land immediately sent a strong signal to landowners that speculation was not going to be a lucrative business in Singapore, and that they’d better find a more productive pathway to profit. At the same time, Singapore introduced development charges which require landowners to pay a levy when the value of their land is increased as a result of planning permission being granted. Current rates are set to capture at least 70% of the land value uplift, which generates land revenues while also discouraging landowners from speculative lobbying over development rights.

These key policies, implemented in the early days of Singapore’s independence, are Georgist to their core. Singapore immediately recognised the need to capture land value for public purposes, the economic threat posed by land speculation, and the injustice of private landowners profiting from government actions. Lee Kuan Yew explained that the above policies were explicitly intended to prevent landowners receiving unearned windfalls:

“First, that no private landowner should benefit from development which had taken place at public expense; and secondly, the price paid on the acquisition for public purposes should not be higher than what the land would have been worth had the Government not contemplated development generally in the area.”

Singapore’s government proceeded to engage in an aggressive process of land acquisition, raising the publicly-owned share of land from 44% in 1960 to 76% by 1976. Today, more than 90% of the land is owned by the state. While many Georgists may balk at the idea of the government controlling so much land, to LKY’s credit, he immediately set about having land rights auctioned off for private use through the ‘Government Land Sales’ program. Land was typically sold on 99-year leases, after which it would revert back into public hands. Again, this sent a clear message to landowners that speculation was not going to be profitable long-term.

Further sources of land-related tax revenues include stamp duties on property transactions and annual property taxes which are levied as a percentage of the annual rental value of a property. Electronic Road Pricing (ERP) charges drivers each time they pass through gantries on heavily-used roads, with prices being higher during rush periods. Although not a policy immediately associated with Georgists, congestion pricing is an excellent example of the application of Georgist analysis to particular economic issues; it requires drivers to compensate society for the privilege of excluding other drivers from scarce slots of space-time on the road. Singapore’s ERP is considered world-class, and has enabled average speeds on expressways to be maintained as high as 65km/h even during peak periods.

Land became a factor of production, a driver for economic growth unhindered by social and political disputes over ownership. There was no landowners’ class to hold back economic development. Government land serves the whole economy as well as public finance, creating the ideal conditions for public housing.

- Anne Haila, once called “the most important Georgist in the World”.

Using Land Rents for All of Society The considerable revenues generated by the above policies have not been frittered away. Instead, they have been put to work for the benefit of all Singaporeans. Proceeds from land sales form part of government reserves, and have been funneled into Singapore’s two sovereign wealth funds, GIC and Temasek. Together, these funds have amassed a net asset value of US$740bn, more than double Singapore’s GDP. This comprises the fourth-largest sovereign wealth fund on the planet, among the ranks of Norway (another Georgist success story), petrostates like the UAE, and China, with a population 250 times larger than Singapore.

GIC & Temasek put these funds to work earning returns on behalf of all Singaporeans. One quarter of Temasek’s portfolio is invested within Singapore, providing capital which helps grow employment and productivity among domestic firms such as DBS Bank, Singapore Airlines and Sea. Like most large funds, they appreciate the value of real estate, and have around US$71bn invested in property, including in one of Asia’s largest real estate companies, CapitaLand. Singapore’s reserves are also deployed for land reclamation and the creation of underground space, with the land value which is created accruing fully into increased reserves.

Freeing Capital & Labour The substantial revenues generated by the above policies of land value capture have provided a huge amount of financial freedom to the government of Singapore. Half of GIC & Temasek’s returns are recycled into the government’s operating budget as the Net Investment Returns Contribution. As depicted below, fully half of all government revenues derive from land in one way or another.